At the ripe age of 50, Silvia Pettem, the American historian and researcher of the city of Boulder, Colorado, realised that she was, in fact, passionate about researching cold cases i.e. criminal cases that had never been solved. After stumbling upon the grave of “Jane Doe, age about 20 years, April 1954” (Jane Doe is a name used for unidentified/anonymous females in North America), Pettem became obsessed with identifying the anonymous woman six feet under and after several years of researching, she established that the person was Dorothy Gay Howard, prompting a new stone to be placed at the grave with her real name.

Several years later and many thousands of miles away, inspired by Pettem’s passion to help solve cold cases, Dave Grimstead founded Locate International, a charity in the United Kingdom in 2019.

“In the UK there are 5,000 unsolved missing person cases that are more than a year old, you’ve also got 1,000 unidentified bodies, and then each year about 1,50,000 individuals go missing – that creates a huge demand on the police and they haven’t got the capacity to be able to go back and review all the cases in depth. Our goal is to provide that additional resource and work in partnership with them,” Grimstead, who has had an illustrious career as a Detective Inspector investigating cases including kidnapping, extortion and child homicide, said in an interview.

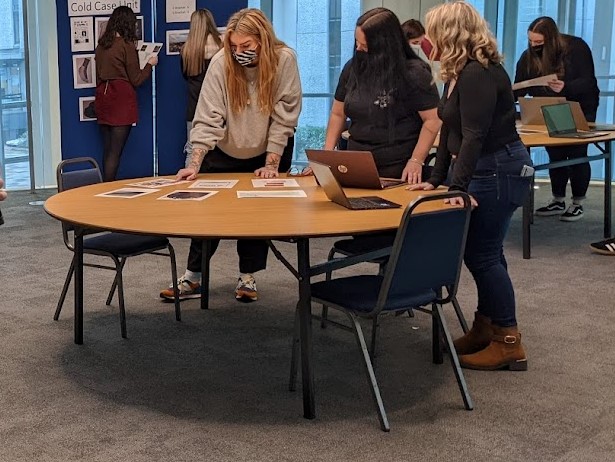

At the heart of it, Locate helps look for missing people with support from a team of experts, specialists and volunteers from local communities. Locate also partners with law enforcement agencies and families to help finding missing people, often in collaboration with universities such as the Cold Case Investigating Team (CCIT) at Goldsmiths that comprises forensic psychology students at the college.

Presently, there are 1,500 “active cases” that could potentially be investigated further. This database of active cases is collected by Locate from publicly available information from the National Crime Agency, Missing People and local police force websites. A dedicated team combs through the information and looks for new leads and whether the cases can be further developed, explains Steve Shepherd, an online safety specialist at Locate with over 25 years of policing experience. Once the cases are identified, a team of collators takes a look to decide whether there’s enough information to pursue the case further. If there is, then the case if allocated to a university cold case team or a community investigation team and is “picked up or run as a case”, explains Shepherd. At the moment, Locate is in partnership with 11 universities, 300 volunteers and eight community teams to work on missing persons cases.

Each team has a leader who usually has some sort of work experience or is at least mentored by somebody who has some sort of experience within missing people or investigation, which means plenty of detectives and ex-detectives are involved. Anybody within those teams can be an investigator as long as they have the time and passion to investigate, since all positions are voluntary. An induction programme, a training programme, and confidentiality agreements are also in place.

There are other volunteers that support the process such as a media team including videographers, musicians and website designers. Locate also has a genealogy team that looks at just genealogy – if x person has a name, who is that person’s mother, father, auntie, uncle, sister, brother and how do they fit into the picture? The charity also works with specialists such as oceanographers who look at tides, and artists who can do facial reconstruction and age progression and age regression.

Locate does not necessarily work in parallel with the police, but “once all the helicopters have gone, and dogs have stopped searching and everything like that, the police never close a case, they put it down for review.” A review in police terms, Shepherd says, is every six months or a year.

“But that’s not an investigation. And if you’re not actually physically going out there and doing any more investigation, then you’re not going to find any more leads. So most reviews just go round around in circles – review it, there’s nothing new, they might put out a press release on an anniversary. And that’ll be it. There’s not actually a team of detectives looking at it and going through the information, asking questions and trying to find new leads,” he says. That is where Locate tries to bridge the gap.

Locate also has a dedicated Family Liaison Team that keeps in touch with and updates the families, something Shepherd says the police are not very good at. Shepherd explains that unfortunately in missing persons cases, there is no law that mandates the police to regularly liaise with families, and Locate has even come across families that haven’t been contacted for over two years.

Locate also actively helps identify bodies that have not been identified, similar to the Pettem case where she identified the anonymous woman buried in Colorado.

Grimstead says that apart from partnering with universities in the UK, Locate is also working with universities in Australia and the police in Germany, who provide support for specialised homicide teams – something the police in the UK also want to get involved with, but haven’t yet.

Shepherd says working as a charity, however, is not without its problems. For instance, even if Locate is able to track down a missing person, Locate volunteers cannot approach or confront them. “That’s not our job. What we do is we generate leads and pass them to the police. It’s the police’s responsibility because there could be things in the background that we don’t know about – has that person fled from domestic abuse? Are they currently associated with a crime that we don’t know about? Does the person intentionally not want to be found?” explains Shepherd.

Other challenges, Shepherd points out, include the fact that some police forces are more forthcoming in sharing information than others. For instance, a case that Locate is working on with the German Police where a man went into the North Sea and the body washed up in Germany, the German Police have supplied Locate with all the case files, autopsy reports, and even provided a secure channel to communicate confidentially.

Then there are other police forces, he says, that have leads on identities of bodies and locations of people but are unwilling to share that information. With one police force, Shepherd wonders, “why after two and a half years, we’ve been asking for case files to be shared with us, and they refuse to do so? I do believe that we are not a threat, but probably a reputational threat to some forces, where they haven’t really done anything and all of a sudden, this charity comes along and goes ‘here we are’.”

Grimstead, though, feels more hopeful. Locate is currently working on a national information sharing agreement with the National Police Chief Council “where they’re going to share information on cases in the future, so all those current issues around information sharing will change because the police see the value in that public community partnership”, Grimstead said. He expects this to be implemented this year and said that the national police chiefs are on board with the plan.

Over the years, Pettem, the American researcher, has been involved with volunteering on cold cases entailing missing persons, helping detectives of the Boulder Police Department and even gives presentations to law enforcement groups on cold-case research. Like Pettem, Grimstead believes in a collaborative effort between the police and private citizens.

“The reality is that things will go wrong with investigation sometimes. They’re never always going to go well,” Grimstead says. “And if it can be corrected at an early stage, it’s better for everyone – better for the families, better for the police. So if we’re able to provide that additional resource, that additional input to correct things much earlier, then generally the police welcome it.”